President Mouri-Kudo Calls for Creation of a European Union University in State of the Commonwealth Address

In her annual State of the Commonwealth address before the National Congress, President Ran Mouri-Kudo delivered a passionate call for deeper academic and cultural integration with the European Union by proposing the creation of a European Union University (EUU) headquartered in Leagio.

“This is our opportunity to make Leagio the academic gateway between Europe and the wider world,” Mouri-Kudo declared to a packed joint session of the Senate and House of Councilors. “Let us not only be a nation of innovation—but also of inspiration, where the best minds from across Europe converge to learn, teach, and collaborate.”

According to the President’s speech, the proposed European Union University would serve as a multinational institution of higher learning with campuses and research hubs across the EU, but with its central campus located in Leagio—tentatively in the state of Arlick due to its growing reputation as an educational and research hub following investments under the Westwood Accord.

The EUU would:

-

Offer degrees jointly accredited by participating EU member states and the Commonwealth of Leagio.

-

Focus on EU-Leagio collaborative research, democratic development, climate resilience, digital governance, and multicultural education.

-

Create a standardized academic framework modeled after Leagio’s Commonwealth University System.

-

Be open to students from both EU and non-EU nations, with special scholarships for students from underrepresented regions.

The proposal follows the enhanced bilateral educational initiatives outlined in the Westwood Accord, which has already strengthened academic ties with the Republic of California. Mouri-Kudo now seeks to expand that vision to the broader European Union.

Under the Constitution of the Commonwealth, the President has the power to propose such initiatives as part of national education and foreign affairs policy, provided it gains legislative approval The President called upon the Ministry of Education and Sports and the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs to jointly draft the required legislation by the end of the summer recess.

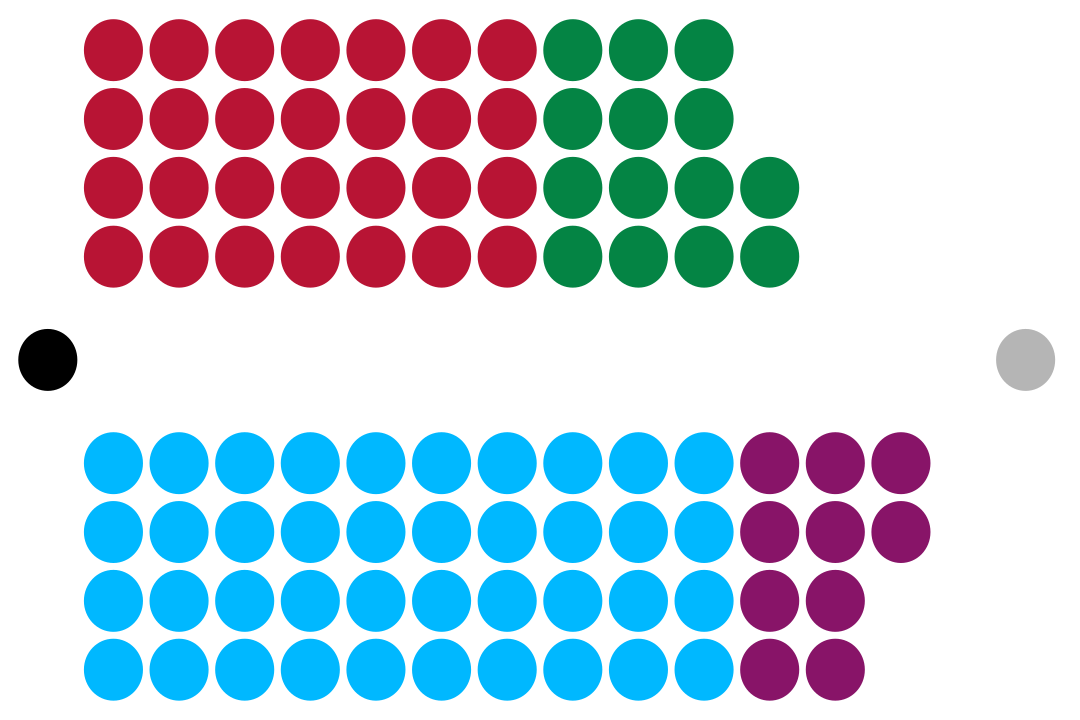

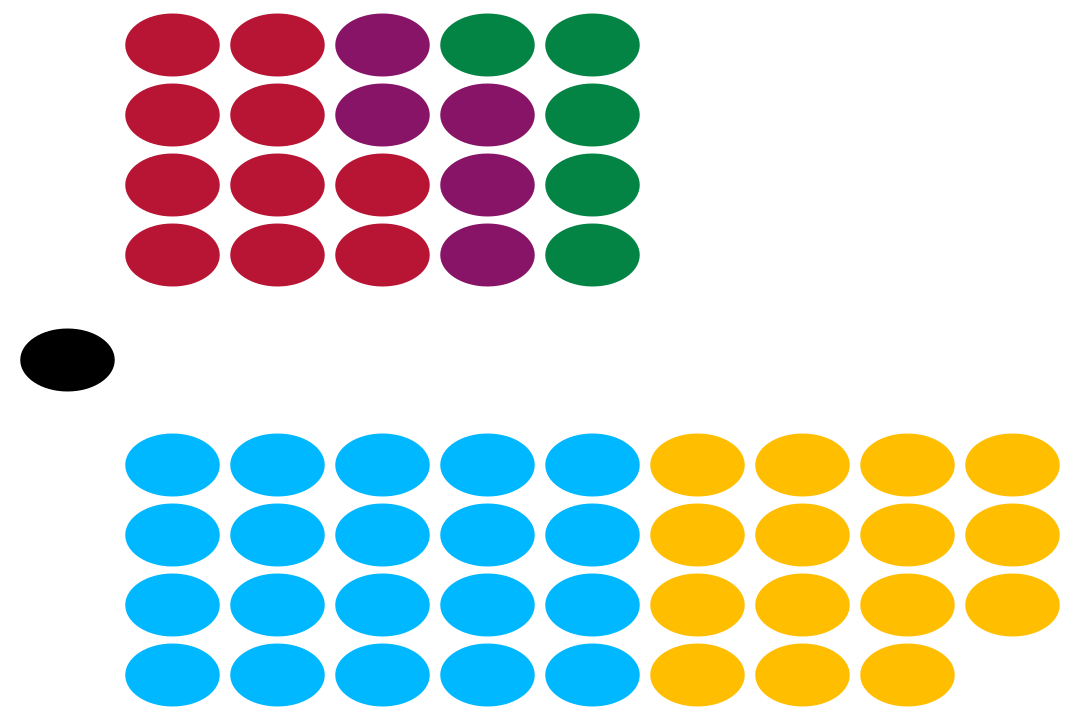

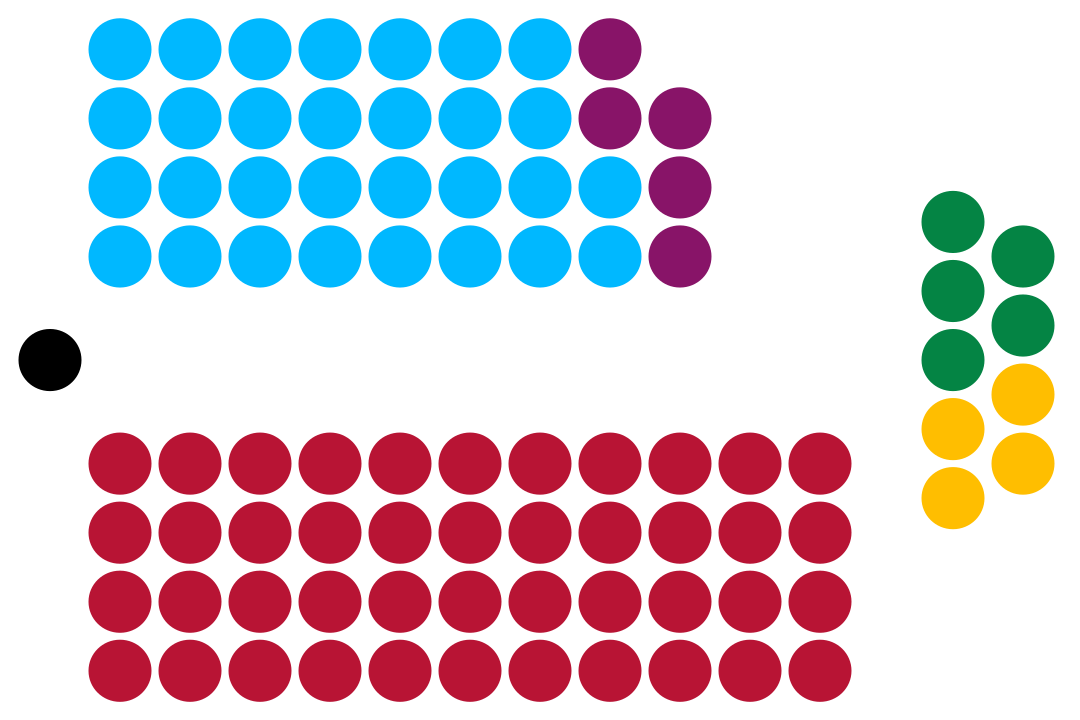

The Progressive Alliance Party (PAP) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP)—both core members of the governing coalition—immediately voiced support for the proposal, citing its potential to promote "multilateral academic excellence" and elevate Leagio’s international standing.

Federation of Centrist Democrats (FCD) leader Kenith Lifejumper gave conditional approval, suggesting the university be funded through grants rather than recurring state expenditure to ensure fiscal responsibility—consistent with the party's principles.

Opposition parties were split. The Green Party and the Socialist Union Party (SUP) welcomed the internationalism of the plan but warned that the EUU must not promote "elitist education." Meanwhile, the Conservative Reformist Party (CRP) expressed concerns that such a project could entangle Leagio further in EU bureaucracy.

Mouri-Kudo concluded her address by calling on the National Congress to act swiftly: “Let us rise above partisanship. Let us envision the future. The European Union University could be the crown jewel of a new, enlightened, and unified Europe—and Leagio must be its heart.”

The House of Councilors is expected to take up initial debate on a feasibility bill in the coming weeks, with budget considerations referred to the Committee on Education and the Committee on Foreign Affairs.