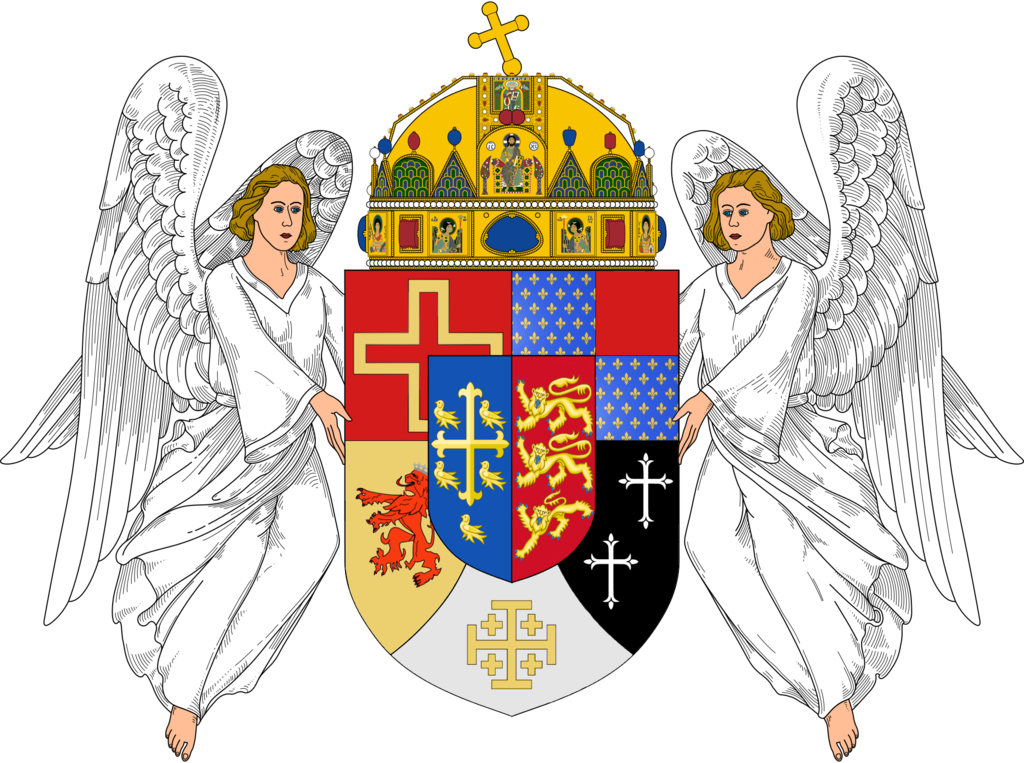

Angleter, Apostolic Kingdom of

-

-

-

HISTORY OF ANGLETER

I. THE 3½TH CRUSADE AND THE BIRTH OF ANGLETER, 1192-1377

The Third Crusade, a predominantly Anglo-French expedition called in response to Saladin’s conquest of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1187, came to an indecisive conclusion in 1192. Though Jerusalem itself was not retaken, the Crusaders did successfully gain a strip of land along the Levant, mostly in present-day Neo-Venetia, and secured the rights of Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land. A number of predominantly English knights opted not to return home in the autumn of 1192 and instead remained in the Levant, forming an ill-organised military order devoted to protecting Christian pilgrims in the region.

Amidst the chaos that consumed the Ayyubid Sultanate after Saladin’s death in 1193, the English knights captured a number of forts in Syria. Aleppo (now Halibon), Hama (now Emathus), and Homs (now Shamel) fell in 1194, and with the help of the German Crusade, Edessa was returned to Christian control in 1197. Though these territories were theoretically conquered in the name of the Crusader states of Antioch and Tripoli, they were in practice governed by the English knights. A French annal of 1210 was the first to refer to these territories as a cohesive entity, calling it the ‘English land in the Levant’, or ‘Angle ter au Liban’.

The weakness of the Ayyubid Sultanate in the early 13th century allowed the Crusader states to consolidate themselves and strengthen alliances with local native Christians. The Crusaders, themselves a conglomeration of knights from various parts of Catholic Europe, relied on the support of Armenians in the Edessa region, Syriac-speaking Nestorians around Calinicon, Maronites along the coast and in the Livan mountains, Greek-speaking Melkites in the main inland Syrian cities, and Syriac-speaking Jacobites in the surrounding countryside, to maintain control of their lands and effectively suppress the Arab Muslim population.

By the mid-13th century, two new external threats developed either side of the Crusader states. The Mamluks, a powerful Egyptian slave caste who had seized power from their former masters; and the Mongols, who had swept through Persia and the Middle East from the steppes of central Asia. Though more sympathetic towards the Mongols, who had a significant Nestorian Christian component, the Crusaders remained cautiously neutral as the Mamluks defeated the Mongols at Ain Jalut in 1260.

This, however, left the Mamluks unchallenged in the region, and free to wipe out the Crusaders. Antioch fell in 1268, sparking the largely unsuccessful Eighth and Ninth Crusades, the latter of which was led by Edward I of England. The few remaining forces of the ‘Angle ter’, however, were able to unite under the command of George, Baron of Maien, who allied with the Ninth Crusade, the Mongols, and Cilician Armenia to relieve Tripoli and defeat the Mamluks at Hermel in 1273. While the Holy Land was irretrievably lost, the Crusaders maintained control over northern Syria, and in 1275 George effectively united the states of Antioch and Tripoli, claiming the new title of ‘Duke of Angleter’.

The united Angleter entered a period of relative peace that allowed George and his successors to establish a Western European style monarchy. While the House of Maien themselves were of German origin, the addition of Ninth Crusade veterans made English the predominant language among the ‘Angleteriques’, the Crusader elite descended from Western Europeans. Intermarriage with native Christians spread the English language, Latin Catholicism, and Western European customs, to the extent that by the mid-14th century around a third of the population were Latin Catholics, with another quarter Eastern Christians.

The death of Duke Albert in 1368 left Angleter in the grips of a succession dispute, which was eventually won by John Noyan, an English-speaker of tenuous relation to the House of Maien, but whose language and claimed descent from Kitbuqa, the Nestorian Mongol general at Ain Jalut, gained him a large following. The chaos prompted a Mamluk invasion in 1375, but John was able to halt the Mamluk advance and rout their army at Tigranakert, and pressed his advantage to establish Angleteric rule over all of the northern Levant by 1377. John was offered a royal crown by Pope Gregory XI, and became King of Angleter on December 4th, 1377, a date chosen as it was the feast of St. Barbara, the patron saint of Syria.

II. FROM KINGDOM TO EMPIRE, 1377-1493

John’s new kingdom was tested in the 1390s by Timur, the Turko-Mongol conqueror who ravaged Persia, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia, but never launched an invasion of Angleter before his death in 1405. Timur destroyed Christian communities in the lands he conquered, prompting a wave of Assyrians, Armenians, Georgians, and Greeks to flee to Angleter and restore the enlarged country’s Christian majority.

For much of the 15th century, Angleter’s Muslim neighbours were weak and divided. The Timurids were constantly gripped by civil war, the Mamluks were in terminal decline, and the Turks of Anatolia were split between multiple different beyliks. This allowed the House of Noyan to expand Angleteric territory into northern Mesopotamia, central Anatolia, and, briefly, western Persia. The border between Angleter and the Ak Koyunlu (White Sheep Turkmen) established in 1476 remains Angleter’s eastern border to this day, giving shape to the province of Fronteria.

The late 15th century saw the rise of the Ottoman Empire to Angleter’s north, promoting King Stanislas I to move the capital from the vulnerable Edessa to the more central town of Palmyra, where he ordered the construction of a new, heavily-fortified city, named New Birmingham in honour of his mother, Sophia de Birmingham. In an even bolder challenge to the Ottomans, who had vanquished the Byzantine Empire forty years prior, Stanislas proclaimed himself ‘Angleteric Emperor’ on 4th December, 1493. He called himself ‘Defender of the Faith in the East’, declared that his empire was the successor to the Byzantine Empire, and called New Birmingham ‘the Third Rome’.

Latin and Byzantine Christendom did not react as Stanislas had hoped. The Pope was outraged that Stanislas had acted without his permission, and the Holy Roman Emperor insisted that he was the only legitimate Emperor in the world. Orthodox Christians, meanwhile, angrily rejected the idea of a Latin Catholic state being the successor to Byzantium. Nonetheless, neither Western nor Eastern Christendom was in any position to challenge Stanislas, and the popularity of the move helped Stanislas halt the Ottoman advance and secure Angleter’s borders.

III. THE KAFIR CALIPHS, 1493-1702

Angleter entered the sixteenth century as a relatively secure Christian empire in the East, and quickly developed an Imperial ideology comparing itself to the third-century Palmyrene Empire, a short-lived Roman offshoot state. To its Muslim neighbours, Angleter was the ‘Kafir Caliphate’, held in as much esteem by Eastern Christians as the Ottomans were by Mulsims.

However, the Ottoman conquest of Mecca and Baghdad, combined with the advent of Protestantism in the mid-16th century, prompted panic in New Birmingham. Angleter was now virtually surrounded by a huge Muslim empire, and its own Christian unity was under threat. Emperor Alexander II sought to repress the Muslim population, which still comprised about 25% of the population; and after a brief Muslim uprising in Yavur in 1547 demanded that all Muslims either convert or leave the country. Almost half left, and the remainder ostensibly converted, although most of those continued to practise Islam in private.This did not, however, resolve the issue of Protestantism. While about 90% of the country was now Christian, as many as a third of these had embraced the Reformation to some degree by Stanislas III’s accession to the throne in 1571. Stanislas introduced Counter-Reformation principles to the Church in Angleter and offered extensive patronages to orders like the Jesuits, reinvigorating Catholic identity and initiating a long decline in the Protestant population, to just 4% today.

The Angleteric state had long enjoyed healthy relations with the Eastern Christian churches, but only the Maronites had entered into formal union with Rome. However, by the early seventeeth century, the Austrian, Polish, and Portuguese states had sought to establish ‘Eastern Catholic’ churches in their territories, and this inspired Angleter to do the same. The Melkite Greek Catholic Church was founded out of the Orthodox Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church was founded out of the Nestorian Church of the East, the Syriac Catholic Church was founded out of the Syrian Orthodox Church, and the Armenian Catholic Church was founded out of the Armenian Apostolic Church, bringing well over half of their clergy and laity with them in each case.

While the Eastern Christians who refused to unite with Rome continued to be tolerated, most other non-Catholic faiths – Islam, Judaism, and Protestantism chief among them – were repressed. Exceptions were made for the faiths of groups who had fled Islamic authorities elsewhere, such as Zoroastrianism and, most notably, Sikhism. A large number of Sikhs fled Mughal persecution to Angleter, to the extent that by 1800, Sikhs formed as much as 10% of the populaton.

Angleter guaranteed its security throughout the early modern era by playing the Ottomans and Safavid Persia against each other, but its borders gradually contracted until they reached more or less its current borders (plus Neo-Venetia) by 1702. Internally, however, Angleter fell apart over the course of the seventeenth century. The infant Stanislas IV became Emperor in 1620, leaving power in the hands of various competing regents, each as venal as the other. As an adult, Stanislas proved unable to cope with the increasing financial pressures facing most European monarchies, and he was forced to abdicate in 1646, ending almost three hundred years of Noyan rule.

Joseph II replaced Stanislas, bringing the House of Carnite to the throne. The Carnites sought to consolidate their power and dismantle any limits on their power, following the European fashion for absolutism. The male members of the Noyan family were almost all executed, and Parliament, always a weak institution, was prorogued in 1657, not to return for another three hundred years.

Joseph’s son, John III, had to contend with the fact that virtually every sector of Angleteric society was outraged at Carnite absolutism. John found few friends in the nobility, the Church, or the emerging merchant class, and his frustration at finding his country increasingly ungovernable boiled over into a series of bizarre decisions. In 1701, a decree replacing much of the judicial system with an armadillo prompted a rebellion supported by virtually all sectors of society, but spearheaded by Wallace Wall, an army general of merchant stock. Wall defeated the childless John, and killed him and his two brothers, at the Battle of Kingswinford on October 4th, 1702.

IV. THE ARMADILLO YEARS, 1702-1713

Wall entered New Birmingham later that day and quickly seized control of the country, annihilating the House of Carnite and ending the reign of the Kafir Caliphs. His efforts to unite the country, however, were foiled by his own ego and a series of strategic blunders. Wall rejected the Imperial crown in favour of the new title of ‘Dominator’, which was widely derided as a show of false humility, and a systematic effort to rename towns, buildings, and landmarks after Wall did little to endear him to the general public. Only symbolic efforts at limiting the Dominator’s power were made, and Wall’s decision not to repeal John III’s infamous armadillo decree, but to instead depose the armadillo with a different, supposedly more loyal armadillo, proved to be another catastrophic misjudgment.

A bloodless coup reinstated the monarchy in 1704 under John IV, a noble of the Martineau family, but his death in 1706 brought his cruel and sexually prolific cousin Ashurbanipal to the throne. He in turn was assassinated, or possibly killed in self-defence, by a prostitute named Catherine in 1709.

In the absence of anybody else, Wall quickly returned to New Birmingham and was acclaimed Dominator again by the locals, endearing himself to the public once again by rewarding the prostitute with the title Baroness Blackrock. However, Wall swiftly lost what goodwill he had gained with increasingly tyrannical decrees, including bizarre ‘guidelines’ on ‘living a healthy daily routine’, a series of increasingly and elaborate military parades, and frequent mass public executions in New Birmingham’s Centenary Square.

Most of the country outside New Birmingham started to ignore Wall’s rule, while the capital turned into an early form of totalitarian dictatorship. When, in 1713, a homeless invalid interrupted one of Wall’s parades to ask the Dominator for alms, Wall responded by viciously beating the man with an elaborate sceptre. The crowd’s anger erupted and a mob overwhelmed Wall and his guards, trampling him to death. Joseph, Duke of Elkhand, the highest-ranking noble present, was acclaimed as Emperor Joseph III, and the country was reunited under a slightly moderated form of absolutism.

The armadillo’s judicial functions were reduced, but remained in a limited form until 1998.

V. THE ELKHAND ASCENDANCY, 1713-1847

The weakening of the Ottoman and Persian empires gave Angleter stability and security during the eighteenth century, and the new House of Elkhand instituted an inoffensive, almost isolationist foreign policy that would prevail until the 21st century.

While Enlightenment thought struggled to take hold in devoutly Catholic Angleter, Emperor George IV’s suum cuique law did guarantee a variety of basic freedoms to his subjects, including freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, habeas corpus, and trial by jury. Various elaborate methods of execution were also abolished in favour of the garrotte and, for military crimes, the firing squad. The various customary legal systems of the various parts of Angleter were mostly standardised under the common law in 1773, a formal land registry was taken the following year, serfdom was abolished in 1778, and the seventeen provinces of Angleter were instituted in 1779.

Angleter also embraced the financial revolution in the early eighteenth century, allowing considerable resources to be channelled towards irrigating much of the eastern desert, opening up new agricultural lands where more modern practices took hold. The population of New Birmingham boomed and a new elite centred around the capital developed. This class pioneered Angleter’s industrialisation, with the first railway from New Birmingham to Asten being opened in 1839.

The Enlightenment, however, bore more radical fruit elsewhere in the world, and by the 1830s many Angleterics took inspiration from the French Revolution, Napoleonic reforms, and early nineteenth-century liberalism. Empress Jane, a fierce absolutist, failed to manage these growing cries of dissent, and in 1847 liberal protests spread across the country, prompting reform-minded nobles and provincial governors to de facto break off from the empire. Jane abdicated and her brother Walter II introduced an elected National Council in a bid to appease the liberals.

VI. PROSPERITY AND HUMILIATION, 1847-1963

Walter was unable to satisfy the rebellious provinces, and Angleter essentially dissolved into a rump state surrounded by independent republics and constitutional monarchies. A reactionary counter-coup in 1850 abolished the National Council, and in 1852, Emperor Julius demoted himself to ‘Grand Marquess’, promising to restore his Imperial title once the country had been reunited.

The Grand Marquessate consisted only of New Birmingham, Quareytene, and Elkhand. Fourteen other states ruled what had previously been the rest of the Angleteric Empire. However, the ongoing decline of the Ottomans allowed the Angleteric nation to avoid foreign conquest, and the general consensus of Angleter’s various rulers in favour of classically liberal economic policies prompted unprecedented economic growth. By 1900, the Angleteric states were on a par with Western Europe in terms of standard of living, although they also suffered Western European standards of inequality.

Between 1911 and 1920 a variety of military actions and diplomatic agreements incorporated much of Angleter back into the Grand Marquessate, but it soon became clear that the tensions that caused the Empire to implode in 1847 had not subsided. Socialist rebellions in 1908, 1912, 1919, 1924, and 1937 rocked the country.

The latter of those uprisings led the young Grand Marquess Stanislas V to co-opt the Levantine Legion, a semi-fascist authoritarian movement led by courtier Peter Gemayel – and declare it ‘the party of the nation’. Gemayel was installed as Chief of Government, and launched a ruthless campaign against the left-wing rebels, conquered four of the remaining six breakaway republics, and restored direct rule over the entire enlarged Grand Marquessate.

The Levantine Legion espoused an ultra-conservative form of Catholic authoritarianism and took responsibility for social and welfare policy, while the monarchy continued to guide economic policy and occasionally stepped in to defend the suum cuique law. While the regime itself was essentially reactionary, this symbiotic relationship marked a crucial step away from absolutism.Embolded after the death of Gemayel in 1955, Stanislas V worked towards the creation of a Constitution in 1963, which established a Consultative Assembly, guaranteed the civil rights of women, and allowed political parties at the local level.

VII. THE CONSTITUTIONAL ERA, 1963-

Gemayel’s successor, Charles Catt, came to dominate the Consultative Assembly, and following the death of Stanislas V in 1971 sought to entrench his authority at the expense of the new Grand Marquess, Joseph IV. In 1973, Catt impelled the Consultative Assembly to declare itself a Parliament, and after a six-month constitutional crisis, Joseph IV signed a new, fully liberal Constitution that allowed for a bicameral Parliament, consisting of an elected Chamber of the Plebeians and a (weaker) hereditary Chamber of the Nobility. Parliament was made supreme over the executive and judicial branches of government, although the monarch retained certain reserve powers.

Catt transformed the Levantine Legion into the Conservative Party, which held power throughout the 1970s, until the Socialist Party, led by Baron Lindett of Murshetpinar, gained power in 1979. Angleter’s conservative ruling elite was thrown into turmoil and retreated into the Chamber of the Nobility, only to find itself unable to prevent genuine democracy taking hold.

The Socialists and their coalition partners, the Social Liberals, introduced judicial reform, proportional representation, and universal healthcare, and also built the first secular schools. They also attempted to negotiate the annexation of the Republic of South Angleter, before conquering it by force in 1980.

By the 1980s, Angleter had rapidly transformed into a modern, liberal, multi-party democracy, and Alan de Lassy brought the CLP – the successor of the Conservative Party – to power in 1989, instituting a range of free-market reforms. The Socialists and the CLP continued to trade power until 2009.

In 2008, Angleter broke with its isolationist tradition and joined the European Union, only for a series of diplomatic gaffes and a bungled attempt to annex Neo-Venetia to lead the country to the brink of war with the major European powers by February 2009. CLP MP Navdeep Khatkar, who had served as Angleter’s first representative in the European Council, left the party and soon swept to power with his new Democratic Party on an anti-war, centrist platform.

Khatkar worked to repair relations with Europe, and Helen Smith became Angleter’s first European Commissioner in 2009, starting a steady stream of Angleterics serving in high office in Europolis as the country became one of the EU’s major economic and military powers. Angleteric officials were instrumental in reforming the EU’s constitution in 2015, and since 2012 Angleter has formed part of an international coalition at war with the rogue state of Dromund Kaas.

In 2011, Angleter restored itself to the level of Kingdom, reflecting the near-unity of the country and its growing confidence as a European power. Khatkar was re-elected comfortably in 2012, but anger at the government’s handling of Dromund Kaas, combined with a terrorist attack that killed nearly 1,000 people in 2014, led to his replacement by Levon Bagratian in 2015, and electoral defeat for the Democrats later that year.

Sam Courtenay, whose Social Democratic Party is a successor to the old Socialists, formed a minority government from then until elections in 2018, when Emryc Isla of the new right-wing populist Citizen Alliance formed a minority government of its own. Angleteric dissatisfaction at setbacks in the European Council and the interminable nature of the Dromund Kaas War have eroded the confidence that spread across the country barely half a decade before, and have fuelled the rise of a populism that promises to reshape the nation once more.

-

LEADERS OF ANGLETER

DUKES OF ANGLETER

House of Maien

1275-1288 | GEORGE I

1288-1309 | JOSEPH I

1309-1312 | FREDERICK

1312-1330 | GEORGE II

1330-1368 | ALBERTHouse of Noyan

1368-1377 | JOHN I

KINGS OF ANGLETER

House of Noyan

1377-1408 | JOHN I

1408-1420 | JOHN II

1420-1441 | ANTHONY I

1441-1446 | GEORGE III

1446-1487 | ELEANOR

1487-1493 | STANISLAS IANGLETERIC EMPERORS

House of Noyan

1493-1502 | STANISLAS I

1502-1510 | ALEXANDER I

1510-1530 | ANTHONY II

1530-1557 | ALEXANDER II

1557-1559 | STANISLAS II

1559-1568 | THEODORA I

1568-1574 | WALTER I

1574-1593 | ANTHONY III

1593-1620 | STANISLAS III

1620-1647 | STANISLAS IVHouse of Carnite

1647-1680 | JOSEPH II

1680-1702 | JOHN IIIDOMINATORS OF ANGLETER

1702-1704 | WALLACE WALL

EMPERORS OF ANGLETER

House of Martineau

1704-1706 | JOHN IV

1706-1709 | ASHURBANIPALDOMINATORS OF ANGLETER

1709-1713 | WALLACE WALL

EMPERORS OF ANGLETER

House of Elkhand

1713-1722 | JOSEPH III

1722-1784 | GEORGE IV

1784-1791 | ELIAS

1791-1818 | JOHN V

1818-1829 | THEODORA II

1829-1847 | JANE

1847-1850 | WALTER II

1850-1852 | STEFANAGRAND MARQUESSES OF ANGLETER

House of Elkhand

1852-1864 | JULIUS

1864-1887 | CHARLES I

1887-1887 | CHARLES II

1887-1925 | JOHN VI

1925-1935 | LEON

1935-1971 | STANISLAS V

1971-2011 | JOSEPH IVKINGS OF ANGLETER

House of Elkhand

2011-2015 | JOSEPH IV

2015-Pres. | GEORGE V

CHIEFS OF GOVERNMENT

1937-1955 | Sir Peter Gemayel, Levantine Legion

1955-1973 | Sir Charles Catt, Levantine LegionPRIME MINISTERS

1973-1979 | Sir Charles Catt, Conservative

1979-1984 | Baron Lindett of Murshetpinar, Socialist

1984-1987 | Dame Janet Norris, Social Liberal

1987-1989 | Harold Peters, Socialist

1989-1993 | Alan de Lassy, CLP

1993-1997 | Sir Steve Ferrers, Socialist

1997-2000 | Jeremy Jones, CLP

2000-2009 | Monty Catt, CLP

2009-2015 | Navdeep Khatkar, Democrat

2015-2015 | Levon Bagratian, Democrat

2015-2018 | Sam Courtenay, SDP

2018-Pres. | Emryc Isla, Citizen Alliance -

-

POLITICS OF ANGLETER

I. THE KING AND THE APOSTOLIC CROWN

The King of Angleter, George V, is the sovereign ruler of Angleter. Historically, the King or Queen was an absolute monarch, although they usually devolved day-to-day power to appointed ministers. However, over the last half century, and especially since the Constitution of 1973, the King has functioned as a constitutional monarch. Under the Constitution, the King retains almost absolute authority to appoint and dismiss Government ministers, and all ministers exercise power in his name, as the Apostolic Crown of Angleter. He is, however, subject to limits on the number of MPs he can appoint as ministers, in order to preserve the independence of Parliament.

The Apostolic Crown holds a range of powers under the Constitution, including the power to dismiss and recall Parliament, and the power to veto legislation. However, the Apostolic Crown cannot do various things, such as raise taxes, spend money, make legislation, or declare war, without Parliament.

This means that the King is also limited, in practice, in whom he can appoint as ministers – any Government would need to command the support of Parliament, and so the King almost always appoints a victorious party leader as Prime Minister and accepts their choice of ministers. If the King were to dismiss his ministers, it would likely cause an election.

Despite his role at the heart of the Constitution, the King generally keeps silent on day-to-day party political matters, in order to maintain his role as a symbol of national unity, and in order to maintain healthy working relationships with all parties. While he chairs Cabinet meetings, he rarely takes part in Cabinet votes. However, the previous King, Joseph IV, spoke out occasionally on issues such as Angleter's accession to the European Union, and it is generally accepted that the monarch's word, while used rarely, carries great weight with the public.

II. PARLIAMENT

Parliament is the supreme legislative body in Angleter. The Constitution frames Angleteric politics as a relationship between the Crown and the nation, and Parliament is the official representative body of the Angleteric nation. It comprises two chambers – the elected Chamber of the Plebeians, and the mostly hereditary Chamber of the Nobility.

The Chamber of the Plebeians has 497 members (MPs), elected in single-member constituencies under the first-past-the-post system, which was reinstated in 2009. All Angleteric citizens over the age of 18 may vote in these elections, except for the King, members of the Chamber of the Nobility, convicted prisoners, bankrupts, and those certified insane. All legislation must first be proposed in the Chamber of the Plebeians, and it is considered by far the more powerful chamber of Parliament.

Legislation in the Chamber of the Plebeians is subject to a rigorous legislative process. A Bill is first debated on its general principles, and then either voted down or sent to one of the Chamber's powerful committees, which then scrutinises the Bill and proposes amendments to it. The whole Chamber then deliberates on those amendments and holds a final vote on the Bill before sending it to the Chamber of the Nobility.

Committees in the Chamber of the Plebeians are large groups of around 30 MPs from all parties, focussed on a specific area. Their roles include scrutinising legislation, questioning Government ministers and holding them to account, and conducting enquiries relating to their area.

The Chamber of the Nobility consists of 275 hereditary noblemen and women, and 24 Catholic bishops, all of whom are required to be non-partisan, although it is generally regarded as quite traditionalist in outlook. It is rare that this Chamber rejects a Bill passed by the Chamber of the Plebeians outright, especially after a confrontation with a Socialist government in 1980 where it was threatened with abolition. It does, however, suggest amendments, which the Chamber of the Plebeians then deliberates on. Bills can go back and forth multiple times before both Chambers agree on a text which is passed on for the King's approval.

III. THE JUDICIARY

Angleteric politics is centred around Parliament and the Apostolic Crown, leaving the judiciary relatively weak. The law is first and foremost interpreted by Parliament itself via further legislation where necessary, leaving little room for 'judicial activism'. The Constitutional Court may impose temporary injunctions on legislation or activity that it rules to be unconstitutional, but it defers to Parliament and the Apostolic Crown as to how any such quandary should be resolved. The Constitutional Court consists of seven members, appointed by the Apostolic Crown, subject to the approval of the Chamber of the Plebeians.

Angleter has a common law system inherited from the English crusaders who founded the country in the early 13th century, although its laws have since diverged considerably and taken on influence from other sources of law, including Byzantine law, Catholic canon law, French customary law, and Islamic sharia and 'urf.

There are three main streams to Angleteric law – civil, criminal, and equity. In criminal law, the lowest court is the Magistrates’ Court, presided over by elected Justices of the Peace, where small offences may be dealt with (only if the defendant pleads guilty), and where preliminary criminal proceedings are held. Cases are then tried before a 15-member jury at the Crown Court; and convicted defendants may appeal the jury’s verdict, or the judge’s sentence, at the Appellate Court, which may adjust sentences, or overturn verdicts and order a retrial.

In civil law, preliminary proceedings take place at the hundred court, which can also deal with smaller claims. Most cases, however, are dealt with by one of seven civil courts – the Court of Matrimonial Causes (family law), the Court of Admiralty (maritime law), the Court of Probate (wills), the Court of Constitutional Causes (constitutional law), the Court of King’s Bench (claims relating to the Apostolic Crown), the Court of Exchequer (debts), and the Court of Common Pleas (all other issues). Appeals from the former four go straight to the Constitutional Court, while appeals from the latter three go first to the Court of Exchequer Chamber.

Equity law exists as a counterweight to the possible harshness, and slow pace of change, of the normal common law system; and can offer remedy to deserving plaintiffs where the current corpus of common law can offer no relief. Equity cases include, but are not limited to, matters relating to trusts, fiduciary law, relief against penalties and forfeiture, bankruptcy, and injunctions. The main equity courts are the Courts of Chancery, whose decisions can be appealed at the Appellate Court of Chancery.

IV. DEVOLUTION

Although Angleter is technically a unitary state, decentralisation is woven into its political system. The country is divided into sixteen provinces, each in turn divided into 'boroughs' (large cities and towns) and 'hundreds' (more rural areas), with the boroughs in turn divided into neighbourhoods. Many of these smaller units operate a form of direct democracy, and all units below provincial level are non-partisan.

Angleteric politics, at least in theory, operates on the principle that each issue should be dealt with at the lowest possible level, and each level of government is mostly self-financing, with some degree of 'equalisation' between richer and poorer areas. Policy making in Angleter usually involves the Apostolic Crown or Parliament setting a framework, and allowing provincial and local governments and legislatures to apply that framework in their own way.

The sixteen provinces have their own Parliamentary system, and a member of the nobility acting as Lord Lieutenant, effectively filling the role of the King at provincial level. However, provincial legislatures and governments are firmly subordinate to national law, although some national laws may be subject to a temporary injunction by provinces in extreme cases.

V. POLITICAL CULTURE

Angleter is generally considered a centre-right country, and has had centre-right governments for most of its democratic history. The Conservative Party, founded in 1973 by Sir Charles Catt out of the ashes of the old Levantine Legion, governed from a socially conservative standpoint for most of the 1970s. It later merged into the CLP, or Conservative and Libertarian Party, which combined social conservatism with economic liberalism, and which dominated Angleteric politics in the 1990s and 2000s. It usually governed with centrist, nationalist, traditionalist, or libertarian coalition partners.

In 2009, the Democratic Party, founded by Navdeep Khatkar in opposition to the Neo-Venetia War, swept to power and became Angleter's main centre-right party, although since its defeat in 2015 it has become increasingly divided between conservatives who identify with the tradition of the CLP, and liberals, who would consider themselves heirs to the Social Liberal Party, which supplied a Prime Minister in the form of Janet Norris in the 1980s, as part of a coalition deal with the Socialists.

Many social conservative parties flourished as the CLP drifted away from the Conservative Party's traditionalist roots, and the most successful of these was the staunchly militaristic and nationalist Angleter National People's Party. This tradition has, however, withered in recent years, torn between the hawkish Democrats and the new brand of anti-war right-wing populism advocated by the Citizen Alliance, which gained power in 2018.

Angleter's left wing has long been conscious of its position as a minority, but often has successfully broadened its appeal to obtain power. The Socialist Party was a social democratic party which focussed on economic issues, aiming not to alarm the socially conservative impulses of many working-class and lower middle-class Angleteric voters. It enjoyed its ascendancy in the 1980s and 1990s, before a massive defeat in 1997 led it to tack to the left, absorbing the orthodox Marxists of the Communist Party.

The Socialists split in 2008, with the Communists re-adopting their old identity, and the Socialists rebranding as the Social Democratic Party. A traditional focus on economic left-wing populism and moderate social policies restored the party's fortunes briefly in 2015, with Sam Courtenay forming a minority government than endured for three years.

The Communists, meanwhile, have sought to broaden their appeal beyond traditional working-class enclaves where the local trade unions happened to have a stronger Marxist tradition. It reabsorbed a Maoist offshoot, the Social Republican Party, in 2011, and a growing alliance with student activist groups led it to join an electoral alliance known as the Coalition for Socialism and Liberation in 2016. The CSL's focus on intersectional activism has found it a new, young voter base, at the expense of some of the Communists' already-dwindling working-class support.